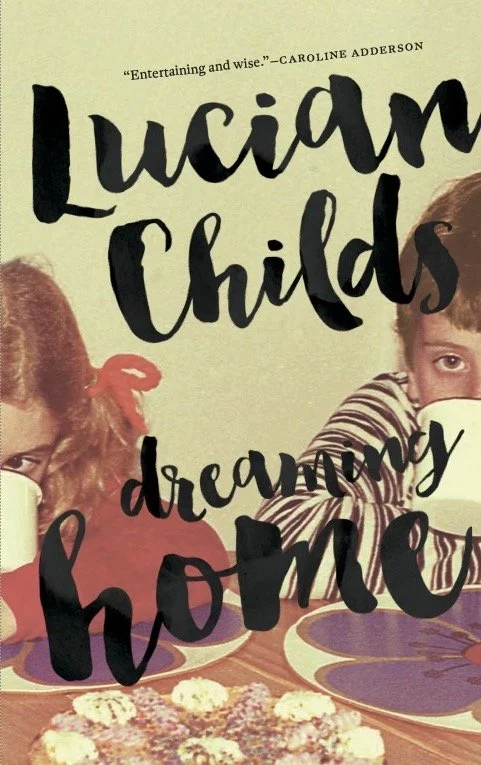

DREAMING HOME

Dreaming Home tackles a number of thorny issues in contemporary life: Conversion therapy, Family Abuse, Depression, Queer Youth Homelessness, PTSD in combat veterans, AIDS in San Francisco and Cultural Identity in 4th Generation Japanese-Americans. Below you will find some of my research that I used in writing Dreaming Home. I hope you find it useful in forming a deeper understanding of the book.

Conversion therapy

While Conversion Therapy, the abhorrent practice that attempts to change a person’s sexuality, is not the subject of the novel, its effects permeate this story of Kyle, his family and his lovers. Though many might think these faith-based or pseudo-psychoanalytical practices a thing of the past, they are still alive and well.

Today, there are just fourteen countries that fully ban the practice. Canada has only very recently made these programs illegal (January 7, 2022). Britain in 2018 announced upcoming bans, but as of this writing there are still none. In the United States, twenty-two states allow the practice (including Texas where Kyle’s conversion therapy takes place.) Six others have only partial bans. Three states are currently litigating against bans passed by their state legislatures.

Ironically, with the exception of people like discredited psychologist Joseph Nicolosi, most leaders of the so-called “ex-gay” movement are or have been gay themselves. Most have recanted their belief in the procedure and have embraced gay life. John Smid, former Executive Director of Love in Action, Michael Bussee, co-founder of Exodus International, Randy Thomas, former executive vice president of Exodus International are some of the many leaders of this movement who have recanted their positions and come together to fight for legislation against its use.

Unfortunately, a new generation of faith leaders has taken up its mantel, such as Jeffrey McCall, founder of Freedom March, who was recently profiled in the Netflix documentary, Pray Away.

Kyle’s descent into “a clouded absence of sensation” and contorted thinking is all too common for those who have participated in these programs. Many individuals report lifelong struggles with depression, anxiety and self-sabotaging behavior. According to a recent study* published in the medical journal JAMA Pediatrics, 47% of recipients experienced severe psychological distress, 65% experienced depression, 67% faced substance abuse, and 58% attempted suicide—all substantial increases over the rates found in the general gay population.

* Humanistic and Economic Burden of Conversion Therapy Among LGBTQ Youths in the United States, Anna Forsythe, PharmD, MSc, MBA; Casey Pick, JD; Gabriel Tremblay, DBA, MSc; et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2022; 176(5):493-501. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0042

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ▼▼

Family abuse, depression and queer youth homelessness

In the novel, in addition to the trauma Kyle experiences at the Ministry, we are told his father frequently loses his temper, scolding his children for small infractions and delivering frequent spankings. In the climactic scene in the second chapter where Kyle’s sexuality is revealed, the father escalates his behavior into a full-fledged beating of his son.

Children who are victims of physical abuse are at serious risk for long-term physical and mental health problems such as depression and anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder, substance use disorders, sleep and eating disorders, and suicide. They may also fall prey to diabetes, obesity, heart disease, poor self-esteem. Many of these symptoms are exhibited by Kyle.

These results are often lifelong, substantially disrupting their ability to connect to others. As Kyle does in the novel, children whose parental relationships are unstable or unpredictable learn that they cannot rely on the help of others. A child who has experienced trauma may have attachment disorders—problems in romantic relationships, in friendships, and with authority figures, such as police officers—again, all features exhibited by Kyle.

Kyle also experiences dissociative episodes, a state often seen in children who have experienced trauma. During the traumatic event itself, they may mentally separate themselves from the experience, as Kyle does after the beating. This feeling of being detached from their bodies and experience may persist throughout their life, especially in stressful situations as we see with Kyle throughout the novel—his periods of staring blankly at the ceiling.

In the novel, Kyle experiences two episodes of homelessness—several months in Houston after graduating high school and a similar period when unemployed in San Francisco. In both cases he takes refuge in his car and avoids having to live on the street. Many other LGBTQ+ youth experience worse outcomes.

According to the True Colors Fund, an organization whose mission it is to alleviate LGBTQ+ homelessness, 4.2 million youth are homeless annually, forty percent of whom identify as LGBTQ+. This is a significant portion of overall homeless youth, since LGBTQ+ youth make up only seven percent of the total youth population. With a paucity of programs directed toward queer youth, many are left to their own resources.

As is the case in the novel, the True Colors Fund notes that family conflict is at the heart of queer homelessness, with 68 percent of homeless queer youth in one study experiencing rejection by their families. The organization goes on to note that there is a shortage of clinics and facilities that specifically address their needs.

Because of this, LGBTQ+ homeless youth are at risk of mental health issues, substance abuse, crime, and victimization. National Network for Youth reports of homeless queer youth, “They are also more likely to experience assault, trauma, depression, and suicide when compared to non-LGBTQ+ populations while also being homeless.”

The outlook for queer youth has significantly improved since the early ’80s when Kyle runs away in the novel. There are an increasing number of organizations that outreach to homeless queer kids today. In addition to the national organizations such as the Trevor Project and the ones mentioned above, those working in San Francisco include the Larkin Street Youth Services, the Lyric Center for LGBTQQ Youth, Dimensions Clinic and more. Even so, there are still many young people who fall through the cracks each year, often to tragic ends.

SOURCES:

The Cost of Coming Out: LGBT Youth Homelessness

PTSD in combat veterans

The effects of conversion therapy on Kyle are mirrored in his father’s PTSD as a result of his imprisonment during the Vietnam War. Soldiers captured toward the beginning of the war, such as Kyle’s father, were often subject to severe physical and psychological torture.

Researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health, Columbia University, The American Legion, and the State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Medical Center* found that many combat veterans continued to experience problems with PTSD decades after the conclusion of the war. Dissatisfaction with their marriages, sex life, and life in general were common, resulting in an emotional numbness and loss of interest in things they once enjoyed. Unsurprisingly, parenting difficulties, domestic abuse and higher divorce rates were found in this population.

Veterans also indicated having more physical health problems, such as insomnia, fatigue, aches, heart problems and colds. Substance abuse, homelessness and suicide were also significant factors many decades after the war. A propensity to startle, irritability and violence, flashbacks triggered by everyday occurrences were also features of the disorder.

Although the experience of the father in Dreaming Home is not explicitly described, many of the symptoms outlined above are implied by his behavior. To worsen matters, PTSD was not officially recognized until the early ’80s—too late to benefit the father in the late-’70s, when the violence initiating the novel’s narrative takes place.

As in the novel, partners and children of combat veterans are also affected. Demoralization in spouses, increased violence and hostility in both sons and daughters have all been reported.

Similar problems are experienced by servicemen and women today. The US Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that PTSD affects about 11 percent of veterans of the war in Afghanistan, and 20 percent of veterans who served in Iraq.

Aggravated by multiple deployments due to policies such as “stop-loss,” suicide rates in US soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan increased alarmingly. From 2009-2011, more American soldiers committed suicide than the combined totals of those killed in the wars themselves.

Unlike in Kyle’s father’s time, treatments for PTSD have standardize with a mix of talk and behavioral modification therapies and ancillary treatments such as eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). In addition, many find hope through peer counseling programs such as those offered by the Wounded Warrior Project, an organization founded in 2003 by John Melia.

Still impediments to receiving care are common. The macho culture inculcated in servicemen and women can stigmatize combat participants with PTSD, encouraging them to tough it out and hide their symptoms. Even today, it can be difficult finding a therapist or program with specific knowledge of the condition. Like the father in the novel, many combat veterans and their families suffer in silence for decades.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and war-related stress

AIDS in San Francisco

Though the intensity of the epidemic has lessened since the early days described in the novel, it is still a significant factor in the life of the city. According to information on the website of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, the organization that serves as the basis for the one in the novel, though the number of infections decreases each year, the city is still home to the largest population in the United States of people living with the HIV virus. More than half of those were classified as having AIDS itself, the late-stage disease marked by extremely low white blood cell counts and/or opportunistic infections, such as pneumocystis or Kaposi’s sarcoma.

The landscape of infection has entirely changed, with most people living with HIV today having significantly depressed viral loads through the use of antiretroviral therapies that were just beginning to become available at the time of the novel. Now, persons living with HIV go on to have long and productive lives. Though sometimes faulted for contributing to risky behavior, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has greatly reduced the likelihood of being infected by the HIV virus.

Though rates of infection and mortality are greatly reduced, the goal of “getting to zero” in San Francisco has still not been attained, particularly in communities of color. Organizations such as the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco Community Health Center; social service entities such as Project Open Hand, Maitri Hospice, Larkin Street Youth Services—many started around the time of the novel and whose work is alluded to in its pages—still have a vital part to play in the health of the city today.

The need for activism still remains. Though the role of ACT UP—AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power—is much diminish, it still advocates for treatments and vaccines. The organization received renewed visibility in 2021 when Farrar, Straus and Giroux published to much acclaim Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show: A Political History of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power New York (ACT UP, New York 1987–1993).

Cultural identity in 4th generation Japanese-Americans

Although not mentioned in the novel, during WWII Jason’s grandmother (Nisei - second generation immigrants) was interned between the ages of five and eight in the Manzanar camp in a remote part of central California. Like most Japanese-Americans at that time, she and her parents (Issei - first generation immigrants) were marked by this experience, choosing to assimilate into mainstream society when they relocated to Sacramento after their release.

Thus deprived of her cultural roots, Jason’s grandmother met and married a Polish-American businessman and continued her and her parents’ quest to become “a good American.”

This assimilation was complete with Jason’s mother (Sansei - third generation immigrants). She attained advanced degrees, found jobs in academia and later married a Jewish-American man nearly ten years her senior.

Jason then is a fourth generation Japanese-American (Yonsei). Mixed-ethnicity individuals, such as Jason, comprise a third of this cohort in one recent survey. There is very little of the Japanese in his look. Diane, Kyle’s mother, rather condescendingly comments that his Asian features are “so slight it is easy for her not to notice.”

Jason exhibits other attributes of fourth generation Japanese Americans. When Jason informally marries Kyle, he continues the practice of intermarriage with non-Japanese that has become established in the Japanese American community since the 1960s. One recent study found nearly 90% of yonsei married into other ethnic groups.

His indifference to his cultural heritage, while not universal, is often found in Yonsei individuals, some of whom were never taught their family histories. Cheryl Lynn Sullivan, an ethnic researcher specializing in the Japanese-American community of California, wrote, “It is common in the Japanese American community not to consider Yonsei Japanese American—they are ‘just plain Americans.’ This is especially true of children who are the offspring of Japanese American–Euro-American marriages.”

Jason’s lack of cultural knowledge is also typical. Most Yonsei are unable to use Japanese and struggle to find their ethnic identity. Jason’s burgeoning interest in Zen practice and Japanese cuisine maps a similar path of many Yonsei. Having been brought up in non-Asian communities—as Jason had—in their later years some find themselves resonating with Japanese traditions they previously never found meaningful.

Jason’s level of professional achievements is also typical with many Japanese-Americans of his generation, who are no longer barred from advancement as were their parents or grandparents. His occasional brushes with ethnic discrimination also tallies with others in his cohort. In one recent study of Yonsei individuals, nearly a quarter of its participants reported having experienced racial stereotyping and discriminatory practices.

SOURCES

How Historical Context Matters for Fourth and Fifth Generation Japanese Americans

NOTES:

Nisei—Jason’s grandmother. Fully Japanese. BORN 1937. Sent to Manzanar camp from 1942 - 1945 from the ages 5 through 8.

Sansei—Jason’s mom. Half Japanese. BORN 1947

Yonsei—Jason, Quarter Japanese. BORN 1970

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ▲▲